Kill Bill, Tom, Dick, and Harry

By Keara Campos | 13.11.2017

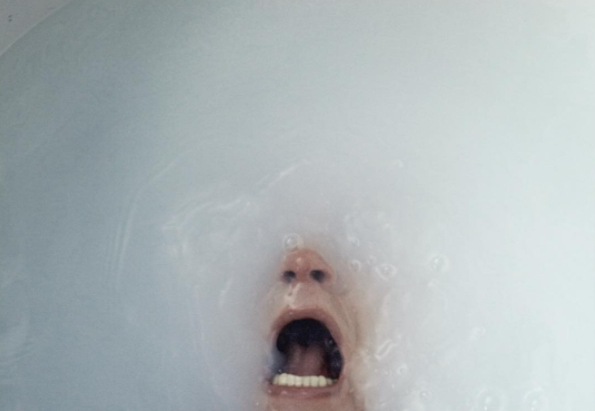

Kill Bill: Volume 1. Dir Quentin Tarantino. 2003.

Ever since the 1992 debut of his crime thriller Reservoir Dogs, Quentin Tarantino has been a household name in the cinematic world. Over the years he has continued to churn out memorable and iconic characters and plotlines, gradually developing his own mythological movie worlds. Kill Bill: Volume 1 and Kill Bill: Volume 2 are two such films. Released in 2003 and 2004, respectively, the Kill Bill movies seemingly represent the emergence of a renewed femme fatale: a woman of few words and unparalleled physical prowess. The Bride, or Beatrix Kiddo, Tarantino’s strong female protagonist played by Uma Thurman, quite literally annihilates any male that stands in the way of her goals. Not only does Tarantino replace the traditional hero with a heroine, he also casts women in the roles of her worthy opponents—and women of colour, at that. These choices appear to indicate an inspiring shift in Hollywood’s portrayal of women on screen, but when critically examined, these female-driven martial arts films are revealed to be increasingly problematic. While a variety of female characters take on novel, expanded roles in these films, their destinies remain beholden to male actors. I foresee a solution to this, which replaces the male authorial perspective with real female experiences. If women directing, writing, and acting increasingly influence cinema, then female realities of violence, sexuality, and life will be more accurately expressed.

Let’s begin with what initially seems to be a new and positive representation of women in major motion pictures. I first saw Kill Bill as an impressionable 17 year old who had just moved away from home. Watching the two volumes back-to-back in my shoebox dorm room remains a vivid memory for me. I remember being engrossed by the strong, independent female character that had one goal: to kill Bill. It was refreshing to see a woman represented as a force to be reckoned with. I was taken with the idea that the character’s goal was to disenfranchise a man, and that this was depicted as achievable. What interested me even more was the fact that Beatrix’s contemporaries along the way were women and particularly, women of varying racial identities. The diversity of these female representations resonated deeply with me, as I myself am a person of colour. Beatrix and her opponents stand in stark contrast to the majority of contemporary female protagonists written to appeal to female audiences (think of the Disney princesses). These stereotypical roles do nothing to represent women as a whole. Rather, they reinforce the clichéd view that femininity is solely synonymous with emotions and weakness and therefore female protagonists can only be damsels in distress, wives, mothers, or sex objects.

The Kill Bill heroine, Beatrix Kiddo, is positioned in league with vigilante protagonists such as Bruce Wayne, Batman, and Dirty Harry. Through Beatrix, Tarantino presents his audience with a multifaceted woman: an expecting mother and bride-to-be but also a merciless killer with an ambitious goal. Within the larger scope of the film world, casting Thurman includes Tarantino within the small percentage of male filmmakers writing leading parts for women. Dr. Martha Lauzen’s report on the top 100 domestic grossing films of 2015 reveals that only 13-15% of male directors and writers create these roles for women (4). Lauzen’s numbers show us that films like Kill Bill are rare and therefore crucial for women in film as they offer a space in cinema where female protagonists and antagonists actually exist.

Kiddo’s character and narrative trajectory make her the ideal hero and an empowering female representation for several reasons. She is physically and mentally strong and displays characteristics that are often only associated with men. She is the antidote to the helpless damsel in distress. Certainly, she is distressed, but she does something about it, as opposed to having another person remedy her situation. Beatrix reflects the ideal characteristics of the vigilante because her main goal—to disenfranchise a despicable man and avenge the loss of her child—is justly retributive. When the most vulnerable of society are slaughtered, the justice demanded becomes proportionally more severe to reflect the crime. Correspondingly, the vengeance the Bride seeks carries “a certain heroic righteousness in her quest to kill her tormentors,” and therefore validates the death of her enemies (Roth 89). Her lack of speaking lines also helps to establish Beatrix’s vigilante status. Urban vigilante films that star famous males typically cast actors who “look better delivering a punch or karate chop than a line of dialogue” (Hopperstand 149). The same holds true for Kiddo in her quest to avenge the loss of her child. As she says herself in Volume 1, “when fortune smiles on something as violent and ugly as revenge, it seems proof like no other that not only does God exist, you’re doing his will.” While the Bride embodies a mentality that is typical of male characters, the audience experiences this journey through the eyes of a female and mother, making Beatrix’s representation of womanhood progressive, empowering, and mutable.

Beatrix emulates characteristics that audiences typically expect from male heroes; superior skills in various forms of combat, and unbelievable reserves of resilience and resourcefulness. The deaths of Kiddo’s nemeses Vernita Green, O-Ren Ishii, and Elle Driver highlight her unparalleled fighting skills. In a Dantean contrapasso style, she defeats each enemy by besting them at their own game; “the knife-fighter Vernita is killed with [the] Bride’s knife. O-Ren is killed by ‘Japanese steel’ [...] And Bill, of course, dies of a broken heart” (Roth 87). Beatrix’s superior skills are on display in the climactic samurai montage where she single-handedly defeats not only the ‘Crazy 88’ army, but also Gogo, O-Ren’s trusted right hand general. In both films, the Bride embodies toughness and ingenuity. She withstands the excruciating training regime of kung fu master Pai Mei and after earning his respect, he teaches her the legendary Five Point Palm Exploding Heart technique. Later, after waking up from a four-year coma, she kills two rapists and escapes from the hospital, all while partially paralyzed, before finally teaching herself to walk again. When Budd, a former member (and one of only two male members) of the Deadly Viper Assassination Squad, leaves her for dead, buried alive in a coffin, she resurrects herself by repeatedly punching the wood until she is bloody, but free. Through Beatrix Kiddo, Tarantino’s audience gets a female protagonist that extends beyond pedestrian female leads: a woman who takes on the role of the vigilante and achieves her goal with finesse and ruthlessness.

Kill Bill: Volume 1. Dir Quentin Tarantino. 2003.

The Bride is more than just a Tarantino hero. She serves as the antithesis to typical pop culture representations of women. Kill Bill is no rom-com. Tarantino shows a type of ‘romance’ where hearts are literally broken. But Beatrix is not the only character in the film challenging traditional representations of femininity on screen. The film’s other female representations include multifaceted women of colour, a deeply marginalized group in mainstream cinema. Both strong and nurturing, Vernita Green is a black woman who steps away from the violent life of Bill’s ‘Deadly Viper Assassination Squad’ to be a mother and wife. Unbound to stereotypes of female passiveness, Tarantino's O-Ren Ishii, a “half-Japanese, half-Chinese American army brat,” entrenches herself within the crime world of Tokyo as the head boss (Tarantino). O-Ren flanks herself with two equally strong women, Gogo and Sofia, who are respectively a fighter and a cunning intellectual. These characters essentially redefine what constitutes ‘feminine’ or ‘female.’ These representations demonstrate that the boundaries surrounding what roles women play in cinema are mutable. The women in this world are able to simultaneously inhabit roles as mothers, wives, killers, and leaders. These women provide an opportunity for female characters to exist in the areas on the spectrum between the traditional, female as an object, and the unorthodox, female as a vigilante.

While Kill Bill’s dynamic women are inspiring, there remains a troubling truth that these portrayals are given to the spectator through a male perspective. The films’ tremendous gore and violence encourages viewers to become engrossed in the on-screen action and to cast aside critical judgement. This aesthetic distancing “through watching an anime section, enjoying elegantly choreographed violence, or at times comfortably recognizing nods to movie action traditions of Eastern and Western male action films” allows viewers to remove themselves from the specifics surrounding said violence (Lavin 109). It is vital to note that the physical brutality in these films is predominantly female-against-female. Furthermore, male forces (both Bill and Tarantino) puppeteer this bloodshed from a safe distance. These women act on Bill’s command and are ultimately pitted against each other. In response to widespread criticism on this subject, Tarantino explained that the films exist in an otherworldly dimension: “this whole movie takes place in a special universe [...] this isn’t the real world [...] this is a movie universe” (Tarantino 126). In making this statement Tarantino justifies a realm where male dominance incites female-versus-female violence. Through a critical lens, it is increasingly obvious that while Kill Bill’s women are allotted roles outside Hollywood’s typical safety zone, their existence is predicated on the sadistic will of male actors.

Kill Bill: Volume 2. Dir Quentin Tarantino. 2004.

Bill’s dominance obviously permeates the films; they are literally named after him. In Volume 1, Bill is an enigmatic figure that the audience anticipates hating because of the crimes he has committed against the Bride. He pulls the strings from behind the scenes and instigates extreme violence such as The Massacre at Two Pines, which left Beatrix in the hospital. However, when we finally meet Bill, he is not the evil, conniving murderer that we expect him to be. Rather, he is depicted as a good father and devoted admirer of Beatrix; Bill even calls her his favourite person. Tarantino completely dismantles the picture of Bill as a murderous psychopath created by Vol 1. and Vol 2. At the end of the two films, the audience comes to understand Bill as more human; he is simply flawed and misunderstood. By depicting Bill in a sympathetic light, Tarantino effectively diminishes the violence and trauma that has been incited by Bill against Bride. Instead of being condemned, Tarantino gives Bill ‘an out,’ a proverbial pass; ‘he’s not a bad guy, he just did a bad thing.’ The issue presented by this softened portrayal of Bill is that, in actuality, he consciously did many bad things. Rather than emphasizing Bill’s cowardly and masochistic tendencies, Tarantino leads the story world to a place where the audience can confuse Bill for kind natured. In forgiving Bill’s sociopathy, the film echoes society’s own willingness to turn a blind eye to the immoral actions of powerful and charismatic men. Here, Tarantino perpetuates a problem endemic to our own cultural understanding of violence against women; that if perpetrated by a ‘redeemable’ man, an assault is not an intrinsically immoral act, but rather, a misstep.

There is a paradox of female representation in Kill Bill’s story world. What initially appears to be a picture of strong women in film transmutes into a typically male illustration of women. Despite including women of colour in its narrative, casting Thurman — a slim, white, blonde, blue-eyed woman — as his lead demonstrates Tarantino’s hesitation to push the boundaries of Hollywood’s aesthetic bubble. The one romantic and consensual sexual relationship he writes into her narrative (with Bill) involves a twisted Oedipal dynamic. The narrative is riddled with nods to a male dominated society, wherein the male perspective sabotages the independence and decisiveness that I earlier celebrated in our female heroine and her contemporaries. The choices that seem to be driven by Beatrix and her counterparts’ own volitions are actually imposed onto them by Bill, and extra-diegetically, Tarantino. A true femme fatale needs to be written and directed by a woman. When these roles originate from a female perspective, the true female experience of how women/womxn interact with violence and sexuality can be accurately depicted.

As a woman, Kill Bill: Volume 1 and Kill Bill: Volume 2 left me wanting. I want to see films made by women and featuring women of varying ethnicities and identities. I want to see females create pictures of what female identity means to women in varying experiences and engagements. At a glance, Tarantino creates powerhouse women who seemingly defy traditional gender roles. These women are the heroines, villains, and mercenaries that we so rarely get to see on screen. Unfortunately, when examined closely, his depictions are rooted in the problems of our male-oriented societies. The solution here is simple: have women create pictures of women. Show strong women, show crying women, show real women, show women of colour, show transgender women, show womxn. Write about women who are mothers. Write about women who are leaders. Write about women who are screenwriters. Write about women who are directors. Write about women who are real. But most importantly, don’t let these depictions come from men, don’t let these images and characters become obfuscated by the male authorial intent. Women in film need to kill their Bills, Toms, Dicks and Harrys; women in film need to overpower the male perspective with their own.

Also Read

Click here for works cited in "Kill Bill, Tom, Dick and Harry"